It is an exciting time for carbon markets. After years of unsuccessfully trying to reach a consensus, mechanisms for Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement received approval at COP29. The door is now open for countries and businesses alike to trade credits on a UN carbon market. This article explores how the carbon credit space has given rise to a business model for technologies that reduce or remove carbon dioxide.

By Eve Pope, IDTechEx

Existing carbon trading markets

Of course, the concept of a carbon market is nothing new. For many decades, the importance of finding a financial mechanism to address CO2 emissions has been recognized, but the global approach has remained disjointed. Compliance carbon trading markets such as the EU ETS (Emissions Trading System), where industries must lower their carbon footprint or purchase additional allowances for unabated emissions, have already been established by governments in several regions. About ¼ of all global anthropogenic CO2 emissions are now covered by some form of compliance carbon pricing.

Businesses not already covered by carbon pricing regulation have been able to access voluntary markets. In voluntary carbon markets, corporates or individuals set climate targets, and voluntarily purchase carbon credits from environmental projects that can reduce or remove carbon dioxide emissions, in order to reach them.

Voluntary carbon credit markets have weathered several scandals pertaining to poor quality credits in recent years. The complex and sometimes volatile nature of these markets has led some to view the carbon credit space as “the wild west”. However, while most of the voluntary market saw a downturn in 2023, corners of the market selling durable, carbon removal credits are flourishing and playing a vital role in supporting emerging technologies such as direct air capture and CO2 utilization in concrete.

Carbon removal credits are restoring trust in voluntary action

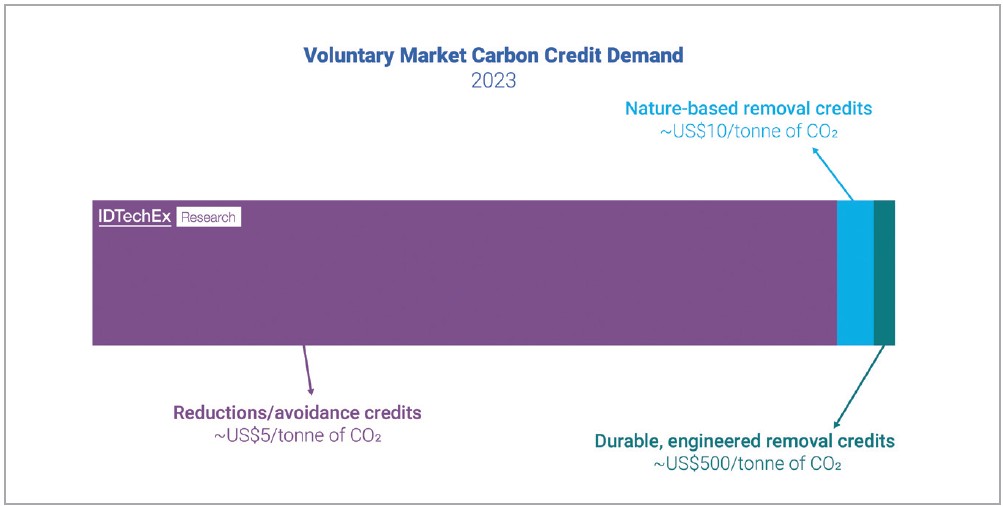

By volume, most carbon credits sold are based on CO2 reduction/ avoidance. Examples of projects that reduce CO2 include avoided deforestation or switching to cleaner cookstoves. However, to calculate how much CO2 has been avoided or reduced, a hypothetical baseline scenario must be established. Inaccurate choice of this baseline has led to some carbon credit projects claiming a much larger environmental benefit than was actually achieved, leading to controversy and greenwashing allegations. For some businesses, trust in this type of credit has been eroded.

But the picture is very different for durable, engineered carbon removal credits – such as those generated from CO2 that is captured and permanently sequestered directly from the atmosphere (DAC – direct air capture) or the biosphere (BECCS – bioenergy with carbon capture and storage). Because of the highly verifiable climate impact and lack of reversibility, corporations are willing to pay top prices for high quality climate action and for the positive press from fostering these nascent technologies. Demand outstrips supply for these lucrative credits, with most sales taking the form of pre-purchase agreements. Durable carbon removal credits have sold for hundreds of dollars per tonne of CO2, and 2023 was a breakout year for sales, with 2024 seeing an even stronger performance.

Direct air capture

Direct air capture is expensive. CO2 levels in the atmosphere are low, demanding large amounts of energy for CO2 separation. Currently, compliance market support for direct air capture is severely lacking. Even in regions where governmental financial support is available, such as the US 45Q tax credit scheme, the money on offer falls below the cost of capturing and storing carbon dioxide. The success of DAC companies has therefore largely been driven by voluntary market support via carbon credit purchases.

For example, in July 2024 Microsoft agreed to purchase 500,000 tonnes of removal credits from Occidental’s 1PointFive Stratos direct air capture facility. When Stratos opens in 2025 in Ector County, Texas, it will become the largest DAC facility in the world (removing 0.5 million tonnes per year of CO2 directly from the atmosphere). At such a large scale, the economics of DAC are expected to improve. Profitable demonstration will be essential to the future of the technology.

CO2-derived concrete

For many CO2 utilization applications, the volume of CO2 recycled is small, limiting revenue generation potential from voluntary carbon credit sales. However, some utilization applications also permanently sequester carbon dioxide – such as stable carbonate formation in the production of CO2-derived concrete. When using biogenic sources of carbon dioxide, such as from biogas or ethanol production, making CO2-derived concrete corresponds to removing carbon dioxide from the biosphere and enables lucrative carbon credit generation.

Most CO2-derived concrete players currently sell carbon credits on the voluntary market to generate additional revenue (or intend to in the future.) By combining this revenue generation with product sales and waste disposal fees, some CO2-derived concrete players are already reporting profitability.

Addressing fugitive emissions

The unintentional nature of fugitive emissions can make their impact on scope 1 CO2 emissions hard to address. Purchasing carbon credits therefore offers a pathway for companies to offset any emissions that are unforeseen or beyond control. Choosing which credits to use has not always been straightforward. The decentralized and overcrowded nature of the voluntary carbon markets has made selecting high quality, verifiable carbon credits difficult for new buyers historically. This unnecessarily complicated marketplace has been a barrier to entry for some companies, but Article 6.4 intends to lay the groundwork for a more unified and standardized carbon market. It is worth noting some projects aimed at reducing fugitive emissions sell CO2 avoidance/ reduction credits in voluntary markets to help with financing themselves, although methodologies and pricing for these credits can look quite different compared to the emerging carbon dioxide removal space.

Outlook

Voluntary market finance will be essential for meeting global net-zero goals, but this space has a history of a volatility and vulnerability. While technologies focusing on direct air capture or carbon dioxide utilization in concrete have been able to rely on carbon credit revenue to foster growth and innovation thus far, only a deeper integration between the voluntary and compliance carbon market spaces will enable these solutions to reach a climate-impactful scale. If these spaces continue to merge, IDTechEx forecasts in its “Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) 2024-2044: Technologies, Players, Carbon Credit Markets, and Forecasts” report that emerging carbon dioxide removal technologies could be withdrawing over 200 million tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere each year by 2035, with the associated credit value exceeding US$30 billion.

This is why the progress on Article 6.4 at COP29 is so vital. A UN carbon market could provide a bigger pool of credit buyers than ever before, and reduce complexity in existing voluntary carbon markets by ensuring methodologies for issuing credits are in line with Article 6 principles and requirements. Although there are still many unanswered questions, especially around ensuring a high-quality credits, COP29 signifies that the international community is ready to embrace carbon markets on a grander and more harmonious level than ever before.

REFERENCES

- https://www.idtechex.com/en/research-report/carboncapture-utilization-and-storage-ccus-markets-2025-2045-technologies-market-forecasts-and-players/1017

- https://www.idtechex.com/en/research-report/carbondioxide-removal-cdr-2024-2044-technologies-playerscarbon-credit-markets-and-forecasts/1007

- https://www.idtechex.com/en/research-report/carbondioxide-utilization-2024-2044-technologies-marketforecasts-and-players/982